Day 64: 8 April 2013

Here I am again, at the end of a sprint. I wanted to put out a quick update, along with a new end-of-sprint build for you guys.

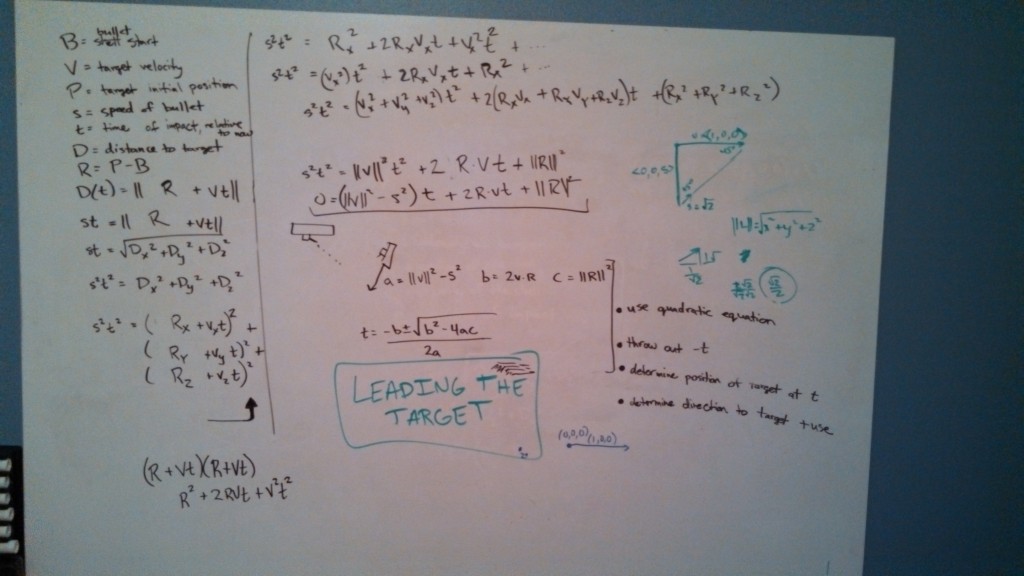

I wanted to share a little development story. So one feature that I wanted to tackle today was to have guns be able to automatically lead their target. This means it will always hit its target dead on, as long as the target doesn’t change its course.

One thing this means is that weapons do not “seek” their target. I had originally intended for it to always be this way, but after seeing this in action, I can tell you that at least some weapons will need to be able to do that. That, or be instantaneous, like a beam weapon. Without it, it becomes a game of who can micromanage their ship’s position and direction in unpredictable ways to avoid being hit. A little of that may be tolerable, but remember, micromanagement is specifically one of the things I wanted to avoid.

Anyway, back to my story.

I sat down to do the math for how to lead your target. This is basically a function of four inputs: the location where the bullet/shell/missile/whatever starts, the location of the target, the velocity of the target, and the speed that the bullet is being fired at:

I got through this whole thing and got an answer. At one point, to simplify things, I defined another variable R as B – P. I thought about what this represented conceptually. B is the position of the bullet initially, P is the position of the target. So R is the relative position of the target from the bullet’s starting location. The problem is, B – P would represent the negative vector–going from the target back to the bullet. It sure seemed like I had it backwards, but I glanced back through my math and didn’t see a real problem. I assumed it was correct, and I went ahead and implemented it.

Which, of course, didn’t work.

So back to my math I went.

Lesson #1: I’ve done enough of this stuff to know I should trust my intuition. It really should have been R=P – B. That gives a vector from the source of the bullet to its intended target.

So I fixed it in my code, and mostly expected things to work this time.

It didn’t. Of course.

By this point, I had been through the math a couple of times, and I was pretty certain the math on my whiteboard was correct. It was something in the code that was broken.

Lesson #2: Unit tests to the rescue! You are, perhaps, tired of me hitting on unit tests as often as I do. The reality is, this game I’m making has helped solidify in my mind that these things are genuinely good for something.

I wrote a simple test: given a bullet start position of <-5, 0, 0>, and a target at <0, 0, 0>, traveling along the +x axis at <1, 0, 0>, with a bullet speed of 2, I know my gun should be firing straight down it’s tailpipe, heading along the +x axis. I ran the unit test, and FAILURE!

Well… at least I could pinpoint the problem. That’s what unit tests are for, right?

So I calculated the example by hand and stepped through the code and compared the two. Guess where I messed up?

It was on the quadratic equation. I didn’t put my parentheses in the right spot. That makes a huge difference. Sometimes, you get the hard parts, but miss the easy parts.

With that fixed, bingo! Everything worked like it should.

Anyway… I’ve got to wrap things up for tonight. The normal end-of-sprint things will need to wait for another day.

Here’s the new build though: http://rbwhitaker.wikidot.com/local–files/sprint-review/100XP-7April2013.ccgame