The Principle of Immedite Recognition

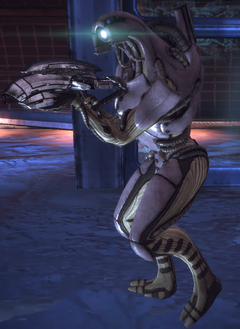

Let’s play a game. Take a look at the three images below, from the game Mass Effect. If you’ve played Mass Effect before, pretend you haven’t. I’m going to ask you a few questions and see if you get them right, even without ever playing the game:

One of these is much tougher to destroy than the others. Which one?

One of these has a fire-based attack. Which one?

One of these is really common. It’s the standard soldier for this species. Which one?

There’s a good bet that you got these all right. You could probably tell the middle one was the toughest, based purely on it’s size. That the last one has the fire-based attack, based on it’s color. And the one on the left looks the most normal and non-threatening (though threatening still the same), and so you’d expect it to be the most common, usually coming at you in groups.

This effect is what I call the Principle of Immediate Recognition. The moment you see something in the game, you have a pretty good idea of what it means. It’s for this same reason that in the arts, most bad guys are dressed in black (or red, or occasionally white, as a counterpoint). Glowing red eyes are always trouble. Glowing blue eyes usually isn’t. (Unless you’re the bad guy.) There are certain things, certain clues, that we pick up on really quickly, either by nature or by conditioning, that transfer a whole lot of information about something very quickly.

The interesting thing here is that in real life, you don’t necessarily have these same clues. If Adolf Hitler had glowing red eyes, do you think Germany would have ever put him in power?

And nature will often use this against us. Some snakes that are perfectly harmless, have a color pattern that looks exactly like snakes that are lethal. And are you going to pick up every black spider with a bulbous abdomen to check for red hourglasses, or just assume that they’re all black widows, and respond accordingly?

This is another one of those times where games shouldn’t always follow reality. You want the player to know quickly and intuitively what things in your game mean. Imagine playing Bejeweled where sometimes, blue gems were actually red in disguise? Or a FPS where all of your enemies looked, you know, like average humans that just happened to have different skills, instead of looking “like a sniper”, or looking “like an engineer.” It would be a disaster. It would be more like real life, but the ambiguity would ruin the fun.

Which brings me back to the game I’m making. In my game, there aren’t ship classes. You can’t necessarily learn things like, this is what a mine layer looks like, or support frigates are the ones that look kind of flat. Mine layers could be big or small. Skinny or fat. Have additional guns or not. And all sorts of ships can be flat, but not very support-frigate-y.

So this presents a bit of a challenge in making my game. I still need players to be able to see a completely randomly built ship and be able to identify it’s strengths and weaknesses quickly.

When you see a tiny ship with big honkin’ engines, your intuition, which tells you that this is going to be faster than a squirrel with a jetpack, must be correct.

When you see a giant fat ship, plastered with guns, leaving no square inch bare, it better be the kind of ship that will turn you into space ash if you get within range of it’s carronades. But unless the enemy has studied his Agrippa (which I have) and spent their allowance/points/whatever on engines as well, that thing is going to be so slow that you should call it a space station instead. You might be able to defeat it by striking in waves and retreating to safety to recharge your shields between encounters.

When you encounter a frigate decked out in satellite dishes and sensors arrays, you can bet your shiny new rail gun that the enemy has known your exact location for nearly the entire battle, and probably already knows your plan. You can safely assume that the deflector shield will be quite operational when your friends arrive.

That a squadron of frigates with a single large spinally mounted cannon means death for your capital ships, while the destroyer blistering with lots of tiny quick firing turrets is gunning for your strike craft.

You get the idea. The game must be done in a way that you know exactly what a ship is going to be like the moment you see it. There’s no need to dig through information sheets to analyze what you’re seeing. (Though that’s probably going to be an option, if you’re a stats kind of person.)

The good news is, by building my ship components right, I think this should be a fairly easy task.

2 Comments

Windwalker

21 February 2013 at 06:50 am

Interesting challange. Indeed after some time, some players might welcome the idea of not knowing what they are against exactly. But of course you can’t design your game for some players who had already invested some hours into gaming.

Maybe the there are some HUD elements over the ships that give clues about it’s basic functions? Like the circle we always see under units, for example. It could have a small mine icon if the ship is a minelayer, or some gun icons for each gun it has, Or a speed arrow for each 10knot speed it has. etc.

And to add to the twist, maybe you need some some sensor ships in relatively close range, to be able to visually see opponent ships abilities and perks. And as you upgrade your sensors, you get more information and range?

Oh…. Are we allowed to throw away ideas like that? Maybe we should keep our ideas to ourselves unless you specifically ask for them, so that we won’t sway your minds flow even by a tiny bit?

RB Whitaker

21 February 2013 at 05:58 pm

Hey, I’m always open to feedback. I want people to sway me. (Of course, it’s my job to make sure that after all of the feedback is considered, that the game ends up being awesome still. To make sure that if the game is being pulled in multiple directions, that it doesn’t get quartered. But this is my ugly baby, so I’ll gladly do that.)

Yes, there will be a HUD that also quickly helps identify what is on board the ship.

Don’t worry too much about this being done so well that the mystery is gone. I imagine being a fleet commander and directing my battle group. At that level, I want my crews and systems reporting accurate information to me about what our enemy has. That’s their job, not mine. My job is just to tell them what to blow up.

But you have a good point here, and I should add a caveat to what I wrote. It’s OK for things to be unknown, but it should be pretty clear that these are unknowns. Like the mystery item boxes in Mario Kart. Clearly marked with a ‘?’ You don’t want things to be misleading. But I’d argue that this is still fitting in with the Principle of Immediate Recognition.

Ohh… another caveat. I’d also make an exception for critical plot points. The story of the Trojan Horse wouldn’t be very interesting if the horse looked exactly like a pile of hiding Greek soldiers. But make sure these are well polished and rare. It’s hard to actually make strategic decisions if you’re always left guessing whether the enemy’s guns are going to shoot artillery shells, nukes, or fish.